The missing piece: Corporate Sustainability Standards in the EU and how they fit with the Investors’ Disclosure Regulation and Taxonomy

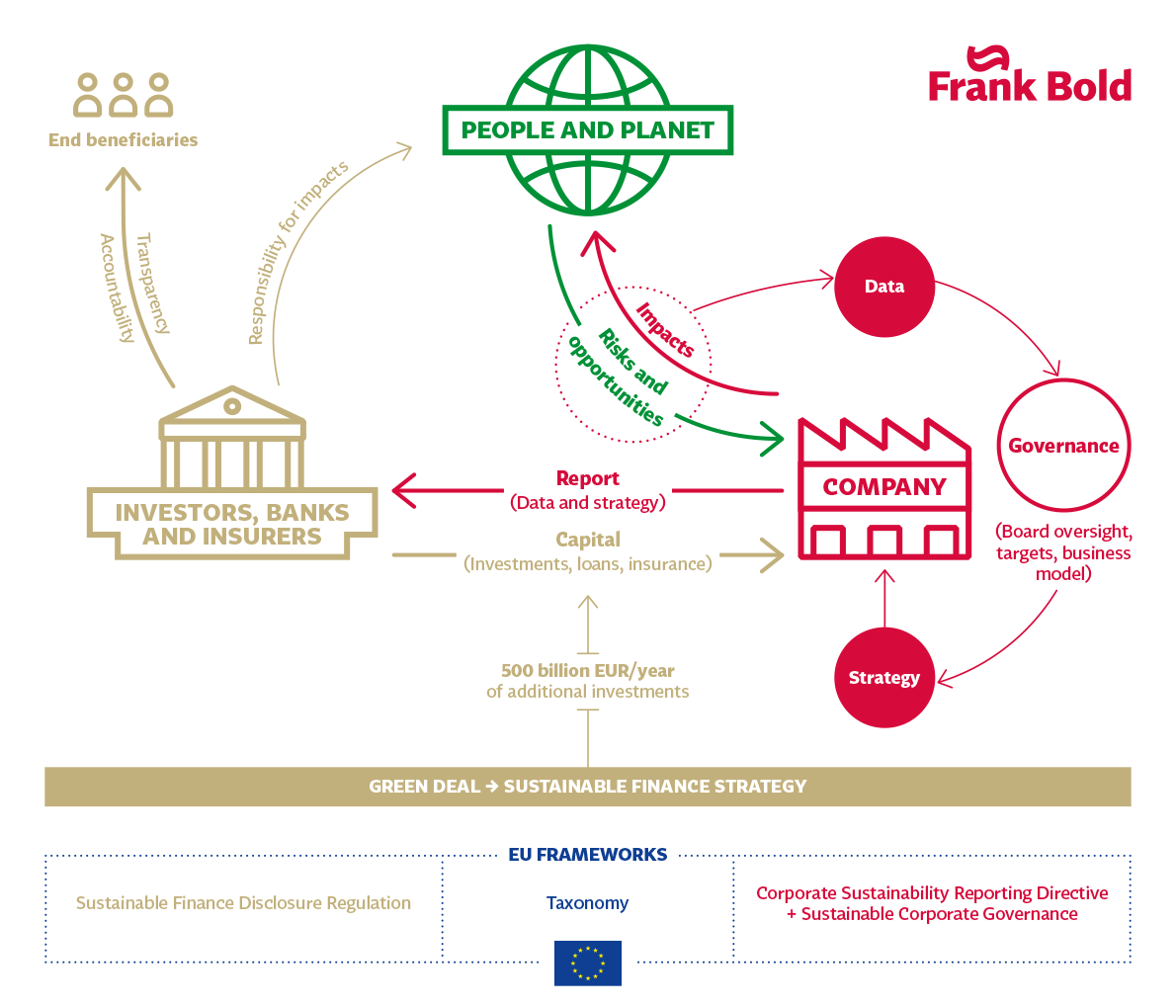

To mobilise sustainable finance for the transformation of the European economy, the EU strategy rests on two complementary lines of action aimed at covering the gap of additional investments needed to meet the EU’s climate objectives (half a trillion EUR every year). First, an overhaul of the incentives in financial markets and corporate governance (these are mainly tackled through the Sustainable Finance agenda and the upcoming Sustainable Corporate Governance initiative). Second, transparency on both positive and negative impacts on sustainability by companies as well as providers of capital.

The strategy to achieve transparency on sustainability impacts relies on the following three pillars:

- The recently proposed Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), previously known as the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), covers companies obligations to report key sustainability data on risks and impacts.

- The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) defines disclosure obligations for investors to show how they factor sustainability risks in their decisions and how they report their strategy, objectives and impacts to end beneficiaries.

- The Taxonomy Regulation classifies sustainable activities (and specifies criteria and reporting requirements) for the purpose of sustainable finance.

Further Information

This article addresses three questions: How do these instruments fit together? What needs to be reported and by whom? What are the gaps that the CSRD will have to close?

What needs to be reported by whom and what is currently missing

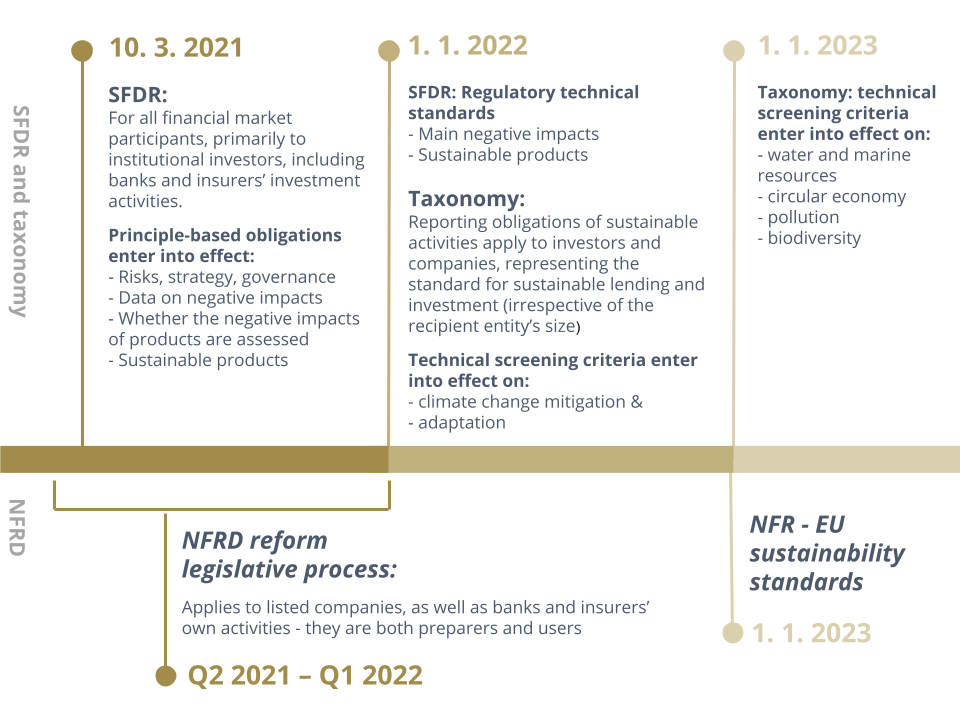

The SFDR applies to all financial market participants, primarily institutional investors, including banks and insurers’ investment activities. Today, the NFRD applies to listed companies, as well as banks and insurers’ own activities – they are both preparers and users of sustainability information. The reporting requirements outlined in the Taxonomy and addressing sustainable activities will apply to both groups, and will become the standard for sustainable lending and investment, irrespective of the recipient entity’s size.

The requirements of the SFDR and the Taxonomy will be supported by technical standards and screening criteria that will enter into force in 2022. Although these are yet to be adopted in law by the European Commission, the draft standards are already available and the EU institutions have recommended investors and companies to follow them. A report by UNEP, FI and EBF already provides practical understanding of the applicability of the EU Taxonomy to banking products. The UN PRI developed case studies sharing insights into how over 40 investment managers and asset owners have worked to implement the Taxonomy on a voluntary basis in anticipation of the upcoming European regulation.

The draft SFDR standards list concrete adverse impact indicators which should be disclosed, and specify how to calculate the impact associated with the investments. The draft screening criteria for the Taxonomy specify the classifications, thresholds and indicators for sustainable activities – that is, activities that substantially contribute to EU environmental objectives and thus qualify for sustainable financing.

What is missing are the corporate sustainability reporting standards, clarifying what needs to be reported by companies on both the risks and impacts of their activities and across their supply chains. They are critical to ensure that companies disclose meaningful and comparable information needed by investors and banks under the SFDR, to fill in methodological gaps on collecting and presenting information, and to reduce companies’ administrative burden. Rients Abma, executive director of Eumedion (Dutch organisation representing the interests of institutional investors), insists on the alignment between the above and stresses that “A harmonized set of ideally global sustainability reporting standards would significantly improve the consistency, comparability, and reliability of sustainability data for us as institutional investors and other users. The revised NFRD should lay the foundation for establishing such a harmonized set of standards.”

The adoption of such EU standards is one of the key objectives of the legislative revision of the NFRD (re-named as CSRD). Another aim of the reform is to ensure that all large and ideally all high-risk companies are included, and not left out of the capital flows that are being mobilised to finance the sustainable transformation and innovation.

The SFDR and Taxonomy rely on the corporate sustainability reporting standards to clarify KPIs, quality criteria and methodologies in four critical areas:

- Minimum criteria for disclosure of companies’ decarbonisation objectives and financial risks related to climate change vis-a-vis the goals of the Paris Agreement. The SFDR requires these to be considered by investors, but it does not specify the quality criteria for disclosure allowing for such an assessment, e.g. timeline and intermediary objectives, scenarios and alignment with Science-Based methodology.

- Methodologies for calculating the impacts by the investee companies, for example with respect to Scope 3 (that is, indirect) GHG emissions, from which the investors should calculate their own investment-related indicators as provided in the SFDR standards. SFDR standards specify only the formula for linking impact indicators to the value of their investments, e.g. with respect to their carbon footprint of their investments, but not for the calculation of the companies’ impact indicators. Currently, many companies that claim to be reporting Scope 3 GHG emissions do so only in a ‘limited’ way, that is, excluding the vast majority of emissions from the presented total.

- What should be disclosed on the company’s due diligence as a minimum safeguard ensuring that sustainable activities and financial products are not connected to severe adverse impacts across the value chains – a condition required by both the SFDR and Taxonomy. The SFDR and Taxonomy merely specify that the due diligence processes should be aligned with the international standards, such as the OECD Guidelines, but don’t clarify what needs to be disclosed at a minimum to give an indication of the quality of a company’s due diligence. David Schilling (Investor Alliance for Human Rights/ICCR) on the quality of information collected by companies, pointed out in a webinar that “The data is meant to enable investors and companies to fulfil their due diligence, and should be focused on not just the policies and practices but also outcomes and impacts on people.”

- Basic set of social indicators and quality criteria addressing relevance, reliability and measurability that both standardised and entity-specific indicators must meet. The SFDR standards outline several additional indicators of adverse human rights impact for companies to choose from, which don’t meet such basic criteria, and whose blind application would lead to meaningless disclosures and administrative burden. Such KPIs, which the corporate sustainability reporting must put into context, include whether a company has a policy against trafficking, number of incidents of severe human rights impacts, and % of operations and suppliers at risks of child and forced labour.

What are the risks and opportunities for businesses in this reform?

The reform of the NFRD (CSRD) and development of corporate sustainability reporting standards are necessary to complete the system for several reasons:

- Sustainable finance needs: Investors, banks and insurers need data from companies to meet their own disclosure requirements, but also – more importantly – to be able to consider the impacts and financial risks and opportunities linked to their investment decisions. In the absence of a legislative mandate and clarification of methodologies, the data available to financiers will continue to be patchy and unreliable (see the research results on 1000 companies here). This is particularly important to meet the objectives of the EU sustainable finance strategy to incentivise investment in activities that substantially contribute to climate mitigation and do not significantly harm the environment or contribute to human rights abuses across the value chain.

- Access to finance and risks to companies’ competitiveness: The NFRD currently applies only to listed companies with more than 500 employees. This leaves a majority of large European companies (around 35 thousand of them), as well as many companies from high-risk sectors, out of the scope. The revised NFRD (CSRD) will specify critical data that will be a de facto condition for access to loans and investments for transformational activities, which in turn will drive market developments. Even a slight delay in the ability to collect and present the relevant data by companies which will not be included in the directive’s scope, will put them (as well as national economies) at a major competitive disadvantage. The combination of the pace and scope of the upcoming economic transformation is unparalleled in history and can leave companies and entire economies utterly unprepared. As Alois Míka, senior energy expert at ČSOB Advisory (KBC Group), puts it: “This decade will decide who will be the winners and losers of this century. The winners will manage to implement sustainable business models, apply artificial intelligence, and digitalize from A to Z. Losers will eventually find themselves in an unfavourable market position, unable to raise external capital.” The banks that have already started to realign their strategies around financing the economic transition have also complained about the need for data from SMEs, as they form most of their clients. Without a legislative mandate and clear standards it will be very difficult for SMEs to report such data.“The CSRD should help our clients’ transition. This is not just about big corporates and listed companies – sustainability data should be required from any company, including SMEs. Big corporates need to assess their supply chain, and the availability of data is critical for that,” explained Ricardo Laiseca, Head of Global Sustainability Office at BBVA.

- Chaotic environment and barriers for SMEs: The current framework of voluntary reporting standards, diverse requirements of individual investors, sustainability rating agencies and buyer companies, and conflicting recommendations of consultants, creates excessive administrative burden for companies. As found by the EU Project Task Force on EU standards, the number of KPIs suggested by existing reporting initiatives exceeds 5000. Listed companies complain about being bombarded with never ending series of requests and forms, and having their sustainability performance rated simultaneously among the top as well as the worst by various benchmarks. Dubbed ‘an alphabet soup’, this context makes it difficult for companies to decide which data to focus on. It also discourages companies’ management to take sustainability data seriously in a business context. This is even more so a problem for smaller companies, some of which need to start their sustainability reporting from scratch; a legislative mandate and clear standards are therefore needed to guide them towards meaningful and effective reporting. “Many companies, especially SMEs and those not supported by international parent companies, don’t have a clear picture of what is expected from them regarding sustainability data. The common problem is that disclosed data often is not standardized and thus not comparable. That is why standards and clear guidelines are essential,” concludes Sara Foršek, Sustainability officer, Raiffeisenbank Austria d.d.

Conclusion

Europe’s corporate sustainability reporting standards are of critical importance to bridge these gaps and thus secure that data is comparable and meaningful, to alleviate companies’ administrative burden, and ensure that smaller businesses are not shut out from access to sustainable finance.

In the absence of such clarifications, companies’ strategies and investors’ decisions will continue to be based on a high degree of uncertainty on both adverse impacts and financial risks.

In this article, we highlight gaps that need to be addressed, in order to improve the quality of company reporting and ensure it is useful for investors, which in turn will enable companies to more easily access sustainable capital and drive capital flows to support climate transition overall.

The key findings are that the picture can be completed by adding:

- a broader scope, covering a wider group of companies

- a clear, simplified set of metrics and indicators

- underlying methodologies for corporate reporting to match those provided for investor disclosure

- details on how to assess whether a company’s targets, timeline and KPIs are in alignment with Paris and SDG goals

- an assessment of minimum social standards in relation to the company’s supply chain

- specification of meaningful disclosures of adverse human rights and environmental impacts

Additional information & materials:

- Integrated overview of upcoming EU legislations requirements. What Data Shall Companies and Investors Report on Sustainability.

- Joint response from 14 leading NGOs to the CSRD proposal.

This is the third article by Frank Bold as part of the series of monthly briefings on sustainability reporting in 2021. The previous article focused on reporting on governance (G of ESG) .