Interview: Rewetting Peatlands to Cut Emissions

Martti Mandel, as Head of the Agricultural Environment Bureau of Estonia’s Ministry of Rural Affairs, works to join up agricultural and environmental issues. In September 2018 he participated in a study tour, Paludiculture in the European Union, which was organised by the Michael Succow Foundation (MSF) and financed by the German Environment Ministry (BMU) under its European Climate Initiative (EUKI).

During the study tour, held on 24–28 September 2018, 36 stakeholders from all three Baltic states visited best practice examples of paludiculture (agriculture and forestry on wet and rewetted peatlands) in the Netherlands and northern Germany. The participants, who came from different levels and represented diverse institutions (ministries, associations, NGOs, practitioners), learned about and discussed the state of the art in paludiculture.

The tour visited a number of demonstration sites such as a project in the Netherlands to cultivate cattail for the production of insulation materials; a project in Hankhausen, Lower Saxony, to cultivate peat moss (Sphagnum) for professional horticulture substrates; a wet forestry project in Schuenhagen, Mecklenburg–West Pomerania, that uses black alder; and a project to rear water buffalo to produce high-quality meat and, at the same time, manage Berlin’s urban wetlands.

During the Berlin leg of the study tour on 28 September, we interviewed Mr Mandel on the status of peatland restoration in Estonia and on his experiences during the tour:

Mr Mandel, you have been taking part in a study tour on peatlands and paludiculture. Why were you interested in going on this tour and why are peatlands so important when it comes to climate change?

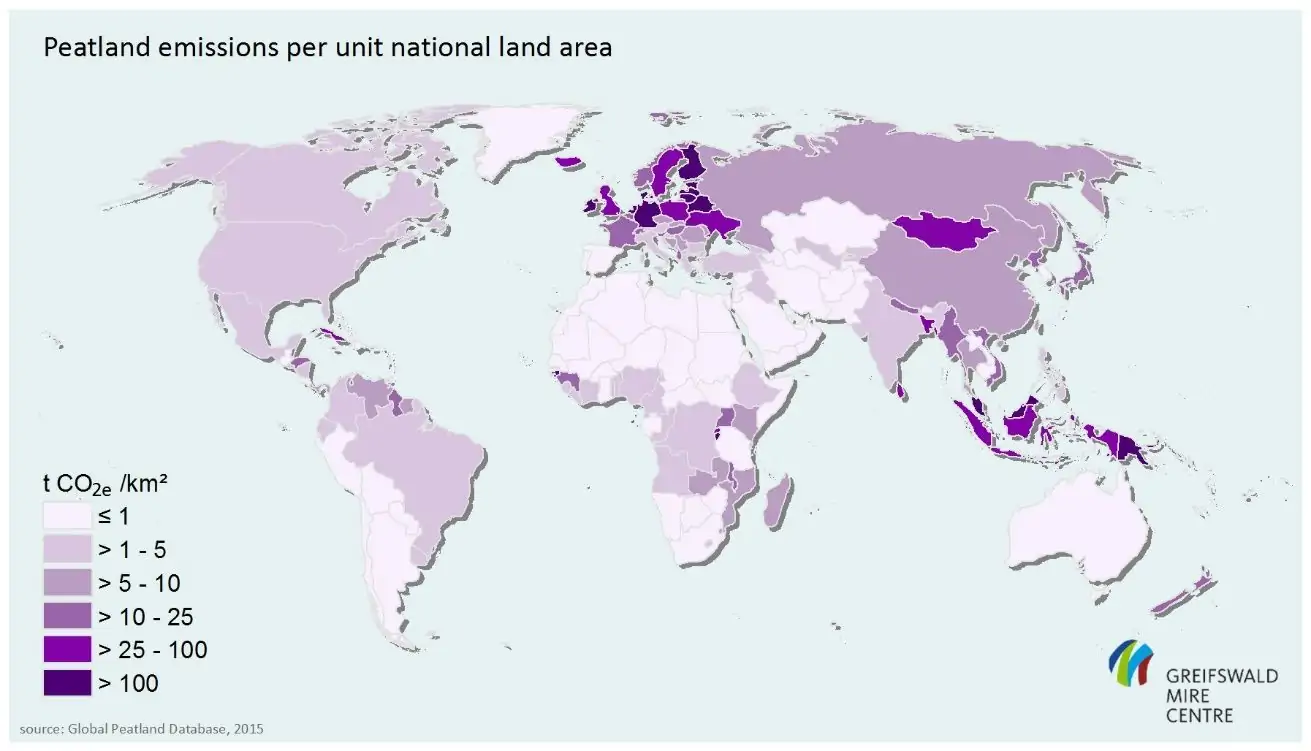

Drained peatlands are a substantial source of emissions. When peatlands are drained and crops are cultivated on them, they become a source of both nitrous oxide (N2O) and CO2 emissions. All the countries that have signed the Paris Agreement – and especially EU countries, which are more ambitious – want to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to mitigate climate change. The rewetting of drained peatlands may be one of the easiest and most cost-effective ways to do it.

What is the situation like in Estonia?

Estimations on drained peatland use vary – some is used as grassland, some as arable land where crops are cultivated. According to our GHG inventory report, we have more than 20,000 hectares of agricultural land on peat soils, but this might be an underestimation. This is a big source of GHG.

What have you done so far to reduce emissions from drained peatlands?

Under our rural development plan, we have measures to support the conversion of these arable lands to permanent grasslands and orchards, which limits the need for land management. This approach will significantly reduce GHG emissions.

To what extent can you reduce emissions by changing the land use?

According to the IPCC Guidelines, the annual emissions from cultivated organic soils could be up to ten times greater than those from grassland organic soils. So, we can reduce emissions a lot. But if we rewet those areas, we could reduce these emissions even more.

How did you get involved in the EUKI study tour on paludiculture and what did you learn from it?

I learned a lot! Before, my knowledge of paludiculture was rather limited, but now I have a much deeper understanding of the subject. I learned that with paludiculture you can turn the rewetting of peatlands into a business. I also learned a lot from the examples we visited in other countries. In other Baltic states, such as Lithuania, the situation is very similar to that of Estonia: there is not much peatland rewetting and there is basically no paludiculture.

Was there an example from the tour that you found particularly striking?

We saw several rewetted peatlands in the Netherlands and Germany and also bioenergy plants. Just today, we went to a water buffalo project near Berlin, which was very interesting. The fact that sites can be used to rear water buffaloes could be attractive to farmers; it is critical to get farmers involved.

Will you be able to apply the knowledge you have gained during the study tour in your ministry’s work in Estonia?

Definitely! Climate and the environment are on the agenda now and will be even more so in the future. We have to find ways to reduce emissions. Having gained a wealth of knowledge about paludiculture and rewetting, I can see this could be one way to do so and a very cost-efficient way at that.

Thank you very much!

Find out more at http://www.succow-stiftung.de/euki-paludikultur-in-den-baltischen-staaten.html (content in German).